How Insulin Resistance Affects Key Organs: Brain

- S A

- Mar 3

- 12 min read

Updated: Mar 10

Part 3

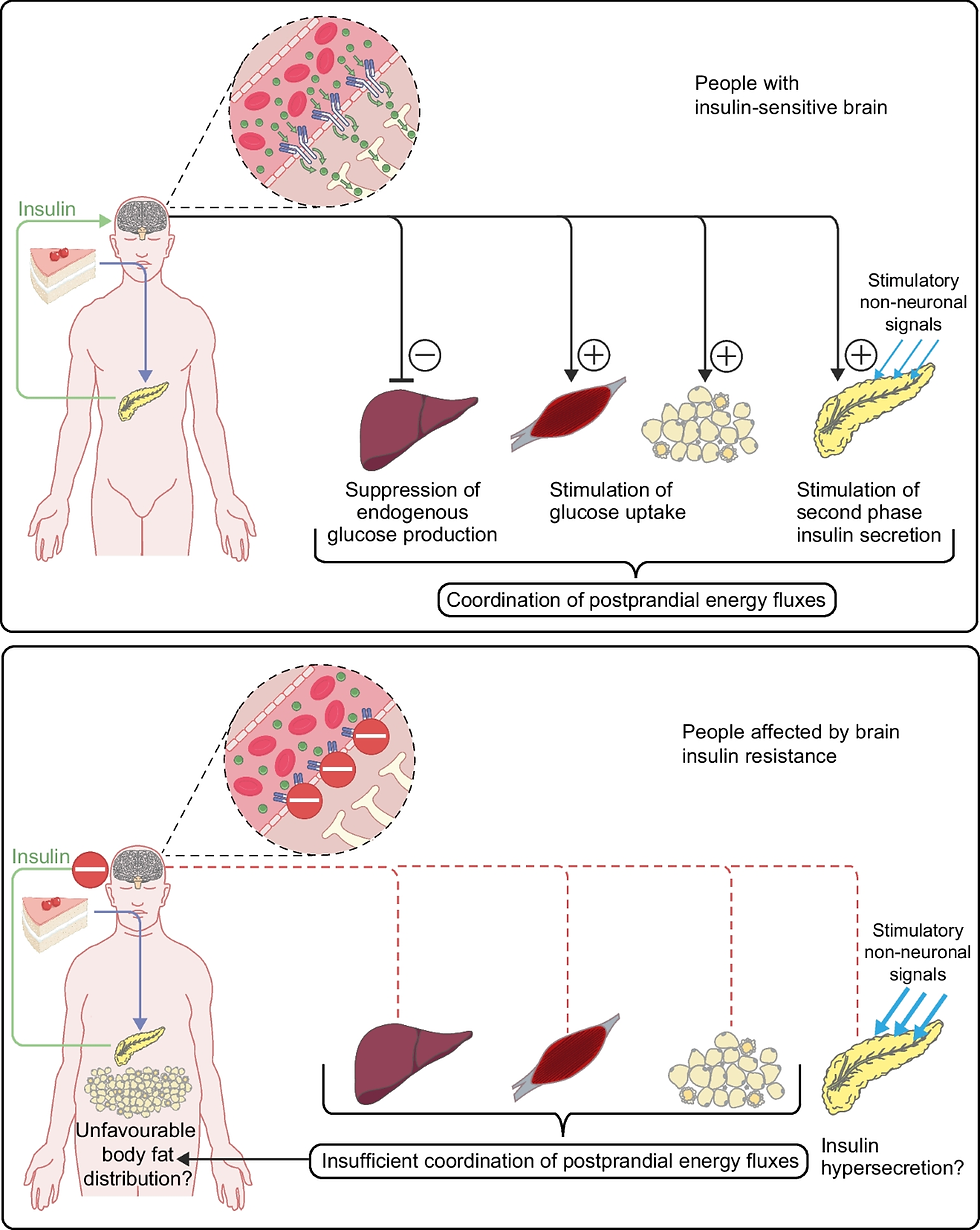

Insulin resistance is often thought of as a metabolic condition affecting the liver, muscles, and adipose tissue. However, the true starting point may lie in the brain, where disrupted signalling leads to a cascade of events that drive overconsumption, metabolic dysfunction, and ultimately, systemic insulin resistance.

In the previous blog, we looked into the sequence of events leading up to Insulin Resistance in major organs of the body. In this blog, we will explore how brain insulin resistance and impaired gut-brain communication set the stage for the metabolic domino effect.

The Brain's Role in Energy Regulation

The brain is the central regulator of energy balance, continuously monitoring glucose and nutrient availability to adjust hunger, satiety, and energy expenditure. The regulation of appetite, metabolism, and food-seeking behaviour involves complex interactions between the hypothalamus and the mesolimbic reward system (dopaminergic pathways). These systems work together to balance energy intake, energy expenditure, and reward-driven eating. Let’s break down their mechanisms in detail.

1. Hypothalamus: The Command Centre for Energy Balance

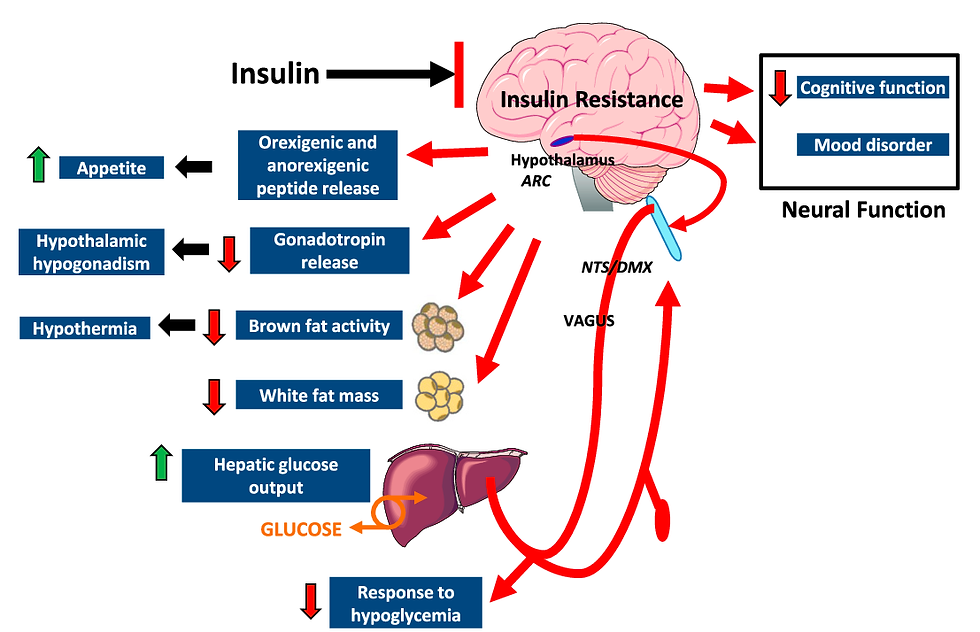

The hypothalamus is the brain's primary regulator of homeostasis, including hunger, satiety, and metabolism. It integrates signals from hormones (such as insulin and leptin) and neural inputs to maintain energy balance.

Key Hypothalamic Regions & Their Roles:

Arcuate Nucleus (ARC): The main hub for appetite control. It contains two key populations of neurons:

AgRP/NPY neurons → Increase hunger and slow energy expenditure.

POMC/CART neurons → Suppress hunger and increase metabolism.

Paraventricular Nucleus (PVN): Receives signals from the ARC and regulates the autonomic nervous system and hormone release.

Lateral Hypothalamus (LH): Often called the "hunger centre," it stimulates feeding behaviour.

How Insulin & Leptin Act on the Hypothalamus:

The brain is traditionally considered insulin-insensitive in most regions, meaning it does not require insulin for glucose uptake. However, insulin and leptin does play a role in brain function, particularly in regions that regulate appetite, such as the:

The brain becomes resistant to insulin, reducing its ability to regulate appetite and metabolism.

There is gray matter shrinkage in key areas involved in appetite control.

The normal neurocircuitry that signals satiety is distorted, leading to increased food intake and cravings.

Leptin (released by fat cells) and insulin (released by the pancreas in response to food) activate POMC neurons and inhibit AgRP neurons, reducing hunger and promoting energy expenditure.

In insulin or leptin resistance, as seen in obesity, the hypothalamus fails to respond to these hormones, leading to persistent hunger and weight gain despite adequate or excessive energy stores.

2. Mesolimbic Reward System: Governing Food-Seeking Behaviour

The mesolimbic dopamine system drives food-seeking and pleasure from eating, especially in response to highly palatable foods (rich in sugars). This system ensures that eating is rewarding, reinforcing behaviour necessary for survival.

Key Components of the Reward System:

Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA): Produces dopamine and sends signals to other brain areas.

Nucleus Accumbens (NAc): Receives dopamine from the VTA and is responsible for feelings of pleasure and reinforcement.

Prefrontal Cortex: Regulates impulse control and decision-making regarding food intake.

Amygdala & Hippocampus: Store emotional and memory-related aspects of food consumption.

How the Reward System Responds to Food:

When we eat highly palatable food, the VTA releases dopamine into the nucleus accumbens, creating a pleasurable sensation.

Sugar causes a strong dopamine release, making these foods highly rewarding.

Overconsumption of these foods can lead to dopamine receptor downregulation, meaning the brain requires more of the same food to experience the same pleasure, leading to overeating and food addiction.

In obesity, this system can become dysregulated, meaning individuals may continue to crave food even when they are full.

Interaction Between the Hypothalamus & Mesolimbic System

The hypothalamus and mesolimbic system are interconnected. While the hypothalamus regulates hunger based on energy needs, the reward system can override these signals, driving food intake based on pleasure rather than necessity.

This explains why someone can still eat dessert after a large meal—the reward system overrides satiety signals.

Implications in Insulin Resistance, Obesity & Metabolic Syndrome

Modern diets rich in sugar, refined carbohydrates, and industrial seed oils cause repeated insulin and glucose spikes. This leads to:

In obesity, insulin and leptin resistance prevent the hypothalamus from properly suppressing hunger, leading to excessive food intake.

At the same time, the reward system is overstimulated by calorie-dense foods, reinforcing cravings and addictive eating behaviours.

Desensitization of the hypothalamus to insulin and leptin: The brain stops responding to signals that regulate hunger, causing persistent overeating.

Dopamine dysregulation: Highly processed foods overstimulate the reward system, leading to compulsive eating behaviours, similar to drug addiction.

Increased gut-derived inflammation: Ultra processed foods alter gut microbiota, leading to endotoxin leakage into the bloodstream (metabolic endotoxemia), which further impairs brain insulin signalling.

This results in a vicious cycle where individuals feel constantly hungry, have strong cravings, and struggle with weight gain and metabolic dysfunction.

As a result, the brain loses its ability to regulate appetite and metabolism properly, leading to excessive calorie intake and setting the stage for systemic insulin resistance.

The hypothalamus and mesolimbic system work together to regulate eating behaviour, but in metabolic disorders, this balance is disrupted. Insulin and leptin resistance impair appetite control, while an overactive reward system drives excessive consumption of palatable foods. Understanding these mechanisms is key to developing effective treatments for obesity, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome.

Image Credit: Springer

Hormonal Regulation of Appetite: The Gut-Brain Connection

Under normal conditions, the brain receives hormonal signals from the gut and pancreas during and after a meal, signalling satiety and regulating food intake. These hormones ensure balanced energy intake by suppressing hunger, slowing digestion, and modulating insulin levels. Below are the key players in appetite regulation.

The brain tightly regulates hunger and satiety through a balance of orexigenic (appetite-stimulating) and anorexigenic (appetite-suppressing) peptides. These neuropeptides are primarily released from the hypothalamus, which acts as the body’s central hub for energy balance.

Orexigenic Peptides (Increase Appetite)

These peptides promote hunger and food-seeking behaviour, especially in response to low energy availability. Key Orexigenic Peptides:

Neuropeptide Y (NPY)

Secreted from the arcuate nucleus (ARC) of the hypothalamus.

Stimulated by fasting, low glucose, and low leptin levels.

Strongly increases appetite and reduces energy expenditure.

Agouti-Related Peptide (AgRP)

Works alongside NPY to enhance hunger.

Inhibits melanocortin receptors (which normally suppress appetite).

Suppressed after food intake.

Ghrelin

The only hormone that stimulates hunger.

Secreted by the stomach when empty, sending signals to the hypothalamus.

Functions:

Increases hunger and food-seeking behaviour.

Promotes fat storage.

Ghrelin & Fasting:

Ghrelin levels increase during fasting and decrease after meals.

Chronic sleep deprivation and stress increase ghrelin, leading to overeating.

Anorexigenic Peptides (Suppress Appetite)

These peptides reduce food intake and signal fullness after meals. Key Anorexigenic Peptides:

Pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) & α-Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone (α-MSH)

Produced in the arcuate nucleus and activated by leptin and insulin.

Binds to melanocortin receptors (MC4R) to reduce food intake.

Cocaine- and Amphetamine-Regulated Transcript (CART)

Works alongside POMC to suppress appetite.

Stimulated by leptin and insulin, indicating energy abundance

GLP-1 (Glucagon-Like Peptide-1)

Secreted by the small intestine in response to carbohydrates, proteins, and fats.

Functions:

Enhances insulin secretion (incretin effect).

Suppresses glucagon release, preventing excessive glucose production.

Delays gastric emptying, prolonging satiety.

Acts on the hypothalamus to reduce hunger.

Therapeutic Use:

Drugs like Ozempic (semaglutide) and Wegovy mimic GLP-1, helping with insulin resistance and weight loss.

CCK (Cholecystokinin)

Released from the small intestine in response to fat and protein consumption.

Functions:

Stimulates bile and pancreatic enzyme secretion for digestion.

Slows gastric emptying, leading to prolonged fullness.

Activates vagus nerve signals to the brain, reducing appetite.

Role in High-Protein/Fat Diets:

Higher protein and fat intake leads to increased CCK, which naturally reduces hunger and promotes longer satiety.

PYY (Peptide YY)

Released by the ileum and colon after meals, especially in response to protein intake.

Functions:

Inhibits hunger by acting on the hypothalamus.

Delays gastric emptying and slows gut motility.

Suppresses ghrelin (the hunger hormone).

Why Protein Helps Satiety:

High-protein meals trigger PYY, reducing hunger more effectively than carbohydrates.

Amylin

Co-secreted with insulin in a 1:1 ratio by the pancreas.

Functions:

Slows gastric emptying, reducing post-meal glucose spikes.

Promotes satiety by acting on the hypothalamus.

Therapeutic Use:

Pramlintide (Symlin) is an amylin analogue used to control blood sugar and suppress appetite.

Takeaway

Understanding these mechanisms explains why high-protein diets promote satiety (due to CCK and PYY), why insulin resistance leads to overeating, and why GLP-1 medications help with weight loss. The balance between orexigenic and anorexigenic peptides is crucial for healthy appetite regulation. Disruptions—caused by insulin resistance, leptin resistance, and ultra-processed food consumption—can drive chronic hunger, overeating, and fat accumulation, setting the stage for metabolic dysfunction.

Image Credit: Semantic Scholar

The Hypoglycemia-Overeating Cycle

Frequent consumption of high-glycemic foods leads to rapid glucose absorption and subsequent insulin spikes. This drives glucose into tissues too quickly, leading to a postprandial drop in blood sugar (reactive hypoglycemia).

This hypoglycemic state triggers:

Increased hunger and cravings for more sugar to rapidly restore glucose levels.

Sympathetic nervous system activation, increasing cortisol and epinephrine, both of which contribute to insulin resistance.

How This Relates to Insulin Resistance and Appetite Dysregulation

Insulin and Leptin Resistance Disrupt Satiety Signals

Chronically elevated insulin and leptin (from frequent high-carb meals and obesity) cause resistance in the brain.

As a result, the brain fails to recognize energy abundance, leading to persistent hunger and overeating.

Ghrelin Stays Elevated, Driving Hunger

Normally, food intake suppresses ghrelin, but insulin resistance can blunt this response.

This leads to persistent cravings and difficulty controlling meal size.

Dopamine and Reward System Override Satiety Signals

Ultra-processed foods hijack the brain’s reward pathways, leading to excessive dopamine release.

This reinforces compulsive eating, even when energy needs are met.

Gut-Brain Signaling Is Impaired

Poor gut health (due to low fiber intake, inflammation, and dysbiosis) disrupts PYY and GLP-1 signaling, reducing satiety.

This results in frequent hunger and overeating.

The Mechanistic Role of Chronic Stress in Insulin Resistance

Chronic stress plays a major role in the development of insulin resistance, primarily through the dysregulation of stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline (epinephrine). These hormones affect glucose metabolism, fat distribution, inflammation, and appetite regulation, all of which contribute to insulin resistance.

1. The Stress Response & Glucose Metabolism

When the body perceives stress—whether physical (e.g., illness, poor sleep) or psychological (e.g., work pressure, anxiety)—the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is activated, leading to the release of cortisol from the adrenal glands.

Cortisol’s Effect on Blood Sugar

Increases glucose production (gluconeogenesis) in the liver.

Reduces glucose uptake by muscle and fat cells.

Promotes lipolysis (fat breakdown), leading to increased free fatty acids (FFAs) in circulation.

This response is beneficial in the short term (for fight-or-flight situations), but chronic elevation of cortisol leads to persistent high blood sugar and insulin resistance.

2. Free Fatty Acids (FFAs) & Lipotoxicity

Chronic stress promotes fat breakdown, releasing excess free fatty acids (FFAs) into the bloodstream.

High FFAs impair insulin signaling in muscle and liver cells, contributing to insulin resistance.

Excess FFAs also accumulate in liver and muscle (ectopic fat storage), further worsening metabolic dysfunction.

3. Cortisol, Adipose Tissue & Visceral Fat Accumulation

Chronic stress increases visceral (belly) fat deposition.

Visceral fat is highly metabolically active, releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) that impair insulin function.

Cortisol promotes fat storage in the abdomen rather than in subcutaneous tissue, leading to a metabolically unhealthy obesity phenotype.

4. Inflammation & Insulin Resistance

Chronic stress triggers low-grade systemic inflammation, which worsens insulin resistance through:

Cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6) blocking insulin signaling pathways.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) causing oxidative stress, damaging insulin receptors.

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, which disrupts cellular insulin response.

5. Stress, Sleep Deprivation & Circadian Rhythm Disruption

Chronic stress often leads to poor sleep, which further exacerbates insulin resistance by:

Increasing cortisol at night (which should normally be low).

Reducing leptin (satiety hormone) and increasing ghrelin (hunger hormone), leading to overeating.

Impairing melatonin, which has protective metabolic effects.

6. Dopamine, Reward System & Stress Eating

Chronic stress alters dopaminergic pathways in the brain, leading to:

Increased cravings for high-calorie, ultra-processed foods (rich in sugar and fat).

Overeating as a coping mechanism, further worsening insulin resistance.

Binge-eating cycles that disrupt normal metabolic regulation.

Summary: How Chronic Stress Leads to Insulin Resistance

Elevated cortisol → Increased glucose production and reduced insulin sensitivity.

Excess FFAs → Lipotoxicity and impairment of insulin signaling.

Increased visceral fat → Inflammation and cytokine release (TNF-α, IL-6).

Systemic inflammation → Direct insulin receptor damage.

Sleep disruption → Worsened metabolic dysfunction.

Dopamine dysregulation → Cravings and overeating.

This explains why chronic stress is a major contributor to insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes. Addressing stress through sleep, mindfulness, exercise, and diet is key to reversing insulin resistance.

Implications for Treatment

Understanding brain insulin resistance opens up new avenues for treating metabolic disease, including:

GLP-1 receptor agonists (such as semaglutide), which enhance insulin signalling and suppress appetite.

Targeting brain insulin resistance through novel therapeutics that restore proper metabolic signalling.

Dietary interventions

Low-carbohydrate diets: Reduce blood glucose fluctuations, lowering insulin demand and improving brain insulin sensitivity.

Whole-food diets: Rich in healthy fats (omega-3s), polyphenols, and fibre, which support brain and metabolic health.

Intermittent fasting: Enhances brain insulin sensitivity by reducing chronic hyperinsulinemia and improving mitochondrial function.

Anti-inflammatory foods: Foods rich in polyphenols, flavonoids, and antioxidants (e.g., turmeric, green tea, berries) reduce neuro-inflammation, which is linked to brain insulin resistance.

Lifestyle interventions like exercise, which improve insulin sensitivity not only in the body but also in the brain.

Thus, brain insulin resistance is a critical yet often overlooked aspect of metabolic disease, linking overeating, obesity, and cognitive dysfunction into a unified framework.

The Evolutionary Perspective

The human brain evolved to function optimally even in prolonged states of fasting or food scarcity. Unlike muscles and other tissues, the brain does not rely on insulin for glucose uptake—its glucose transporters (GLUT1 and GLUT3) operate independently of insulin. This was a crucial adaptation for survival, ensuring that even in times of prolonged fasting, the brain received enough energy to function.

As long as blood glucose remains above 50 mg/dL, the brain continues to function normally. This evolutionary adaptation allowed early humans to endure long periods without food, such as during hunting or gathering, without cognitive impairment.

Under normal conditions, a fasting glucose level of ~80 mg/dL is sufficient for brain function.

Even if glucose levels drop to ~50 mg/dL, the brain remains saturated with glucose and functions optimally.

If glucose falls below 40 mg/dL, brain function becomes compromised, leading to confusion, dizziness, and potential unconsciousness.

This mechanism provided a survival advantage. When food was scarce, humans could still think, plan, and hunt effectively, relying on stored body fat and ketones for energy.

Modern Context: The Role of Hyperinsulinemia

In today's world of constant food availability—especially ultra-processed, carbohydrate-heavy foods—this finely tuned system is disrupted. Unlike in ancestral times when blood glucose was tightly regulated, modern diets cause:

Frequent insulin spikes due to high sugar and refined carbohydrate intake.

Reactive hypoglycemia, where excessive insulin secretion leads to a rapid glucose drop, triggering hunger and overeating.

Brain insulin resistance, impairing appetite control and leading to further overconsumption.

Ironically, while the brain is insulin insensitive for glucose uptake, it does respond to insulin for signalling satiety. When insulin resistance develops, the brain stops recognizing insulin’s appetite-suppressing effects, driving further caloric intake and metabolic dysfunction.

This mismatch between our evolutionary adaptations and modern dietary habits sets off the entire cascade of insulin resistance, beginning in the brain and spreading to muscle, adipose tissue, liver, kidneys, and eventually the pancreas.

By understanding this evolutionary context, we can see why reversing insulin resistance requires aligning our modern diet and lifestyle with the metabolic conditions our bodies were designed for.

How to Prevent the First Domino (Brain Insulin Resistance) from Falling

Since brain-gut dysfunction is the first step in the cascade of metabolic dysfunction, addressing it early can prevent downstream insulin resistance in the muscles, adipose tissue, liver, kidneys, and pancreas. Here’s how to tackle the root cause:

Strategy | Why? | How? |

Optimize Nutrient Timing and Meal Composition | Frequent spikes in glucose and insulin lead to dysregulated appetite control and reactive hypoglycemia, driving overeating. | - Prioritize protein and healthy fats at meals to slow digestion, enhance satiety, and reduce insulin spikes. - Limit refined carbohydrates and fructose, especially ultra-processed foods that overwhelm the brain’s satiety signalling. - Incorporate fibre-rich foods (vegetables, nuts, seeds) to slow glucose absorption and prevent rapid blood sugar fluctuations. - Time meals appropriately—avoid constant snacking and late-night eating, which disrupts insulin signalling. |

Regulate Dopamine and Reward System Response | Ultra-processed foods hijack the brain’s dopamine system, reinforcing addictive eating behaviours and making appetite regulation harder. | - Avoid hyper-palatable foods (chips, pastries, fast food, sodas) that combine sugar, fat, and salt to trigger cravings. - Reduce artificial sweeteners, which may perpetuate cravings and disrupt insulin signalling. - Engage in dopamine-regulating activities such as exercise, meditation, or cold exposure to rebalance the reward system without food dependence. |

Prioritize Sleep and Circadian Rhythm Alignment | Sleep deprivation increases brain insulin resistance, disrupts hunger hormones (increases ghrelin, decreases leptin), raises cortisol, and alters glucose metabolism. | - Aim for 7-9 hours of quality sleep per night. - Maintain a consistent sleep-wake cycle, aligning with natural light exposure. - Avoid screens and artificial light at night, as they impair melatonin production and disrupt metabolic health. |

Practice Intermittent Fasting or Time-Restricted Eating | Fasting helps reset insulin sensitivity, lowers brain inflammation, and improves metabolic flexibility. | - Start with a 12-hour overnight fast, gradually extending to 14-16 hours if tolerated. - Avoid excessive snacking, allowing insulin levels to return to baseline between meals. - Incorporate occasional longer fasts (24+ hours) if suitable, to promote autophagy and mitochondrial efficiency. |

Engage in Regular Physical Activity | Exercise enhances insulin sensitivity in the brain and body, improving glucose metabolism and appetite regulation. | - Incorporate daily movement, including walking, strength training, and aerobic exercise. - Exercise in a fasted state occasionally to enhance metabolic flexibility. - Prioritize strength training, as increased muscle mass acts as a glucose sink, improving overall insulin sensitivity. |

Manage Stress and Optimize Mental Health | Chronic stress elevates cortisol, which increases glucose levels and promotes brain insulin resistance. | - Practice mindfulness, meditation, or deep breathing to lower stress. - Engage in social activities and nature exposure, which support brain health and reduce stress-induced eating. - Limit excessive screen time and doom-scrolling, which overstimulates the brain and contributes to poor sleep and stress. |

Support Brain Energy Metabolism with Ketones | The brain functions efficiently on ketones, which can bypass insulin resistance and improve cognitive function. | - Incorporate ketogenic or low-carb meals, allowing the body to produce and utilize ketones. - Use exogenous ketones (if necessary) to supplement brain energy, especially during fasting periods. - Consume medium-chain triglycerides (MCT oil) to provide an alternative fuel source for the brain. |

By addressing these key areas, we can prevent brain insulin resistance from taking hold, thereby stopping the entire cascade of metabolic dysfunction before it begins.

Conclusion

The brain is the first domino to fall in the cascade of insulin resistance. By disrupting appetite control and promoting overconsumption, modern diets high in sugar and ultra processed foods initiate a metabolic chain reaction that affects every major organ system.

Addressing brain insulin resistance through diet, exercise, and lifestyle interventions is key to breaking this cycle before it progresses to full-blown metabolic disease.

In the next blog, we will explore skeletal muscle's role in insulin resistance—the body's largest site of glucose disposal and a crucial factor in metabolic health.

*Disclaimer:

The information provided in this blog is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as medical advice. While every effort is made to ensure accuracy, the content is not intended to replace professional medical consultation, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the guidance of a qualified healthcare provider with any questions regarding your health, medical conditions, or treatment options.

The author is not responsible for any health consequences that may result from following the information provided. Any lifestyle, dietary, or medical decisions should be made in consultation with a licensed medical professional.

If you have a medical emergency, please contact a healthcare provider or call emergency services immediately.

コメント