Picking up from the earlier blog, the question of existence—"Why does the universe exist at all?"—has captivated thinkers for centuries. This is not about how the universe came to be, such as through the Big Bang, but rather about why there is anything rather than nothing. Philosophical and scientific traditions have grappled with this profound inquiry, and Advaita Vedanta offers a compelling perspective.

Western Perspectives on Reality

John Wheeler's "it from bit" idea suggests that matter emerges from information, challenging the traditional view of reality as purely material. Aristotle's concept of hylomorphism further posits that reality comprises both substance (the material) and structure (its form), echoing the material and informational interplay that defines modern physics.

Subjective Idealism and Samuel Johnson’s Rebuttal: This highlights some intriguing Western perspectives on reality that resonate with modern developments in physics, philosophy, and consciousness studies. This reminds us of Samuel Johnson in England. When he was told about Bishop Berkeley's theory—subjective idealism, which claims that the external world is merely an idea in our minds and not materially real—Johnson famously kicked a rock and declared, "I refute it thus!" To him, the rock's undeniable physicality disproved Berkeley's claim. However, this was before the discovery of atomic structures. Modern science reveals that what appears solid, like Johnson’s rock, is mostly empty space. Atoms, protons, neutrons, and quarks are not tangible particles but bundles of properties and interactions.

The Problem of Consciousness

Jim Holt and the Mathematical Limits of Consciousness: Jim Holt highlights a key limitation in understanding consciousness: it cannot be quantified or modelled mathematically. Unlike physical phenomena such as particle behaviour or cosmic motion, consciousness remains irreducible to equations. Its inherently subjective nature defies external descriptions, marking it as a distinct aspect of reality.

Other physicists, such as John Wheeler and Sir Arthur Eddington, explore the idea that the universe might not be composed of tangible "stuff" but is, rather, a set of observable structures and phenomena — observations being our only access point to reality. The quote from Wheeler about "reality consisting in our observations" echoes this view, suggesting that what we perceive as the external world may be a collection of registrations rather than solid objects.

Physicist Sir Roger Penrose adds a radical perspective, proposing that the universe is fundamentally mathematical. He describes a triangle of interdependence between consciousness, the universe, and mathematics. He suggests the universe’s structure is accessible to mathematics because it might be mathematics. Galen Strawson suggests the real mystery isn’t consciousness but the nature of matter itself, as it increasingly eludes a definitive explanation.

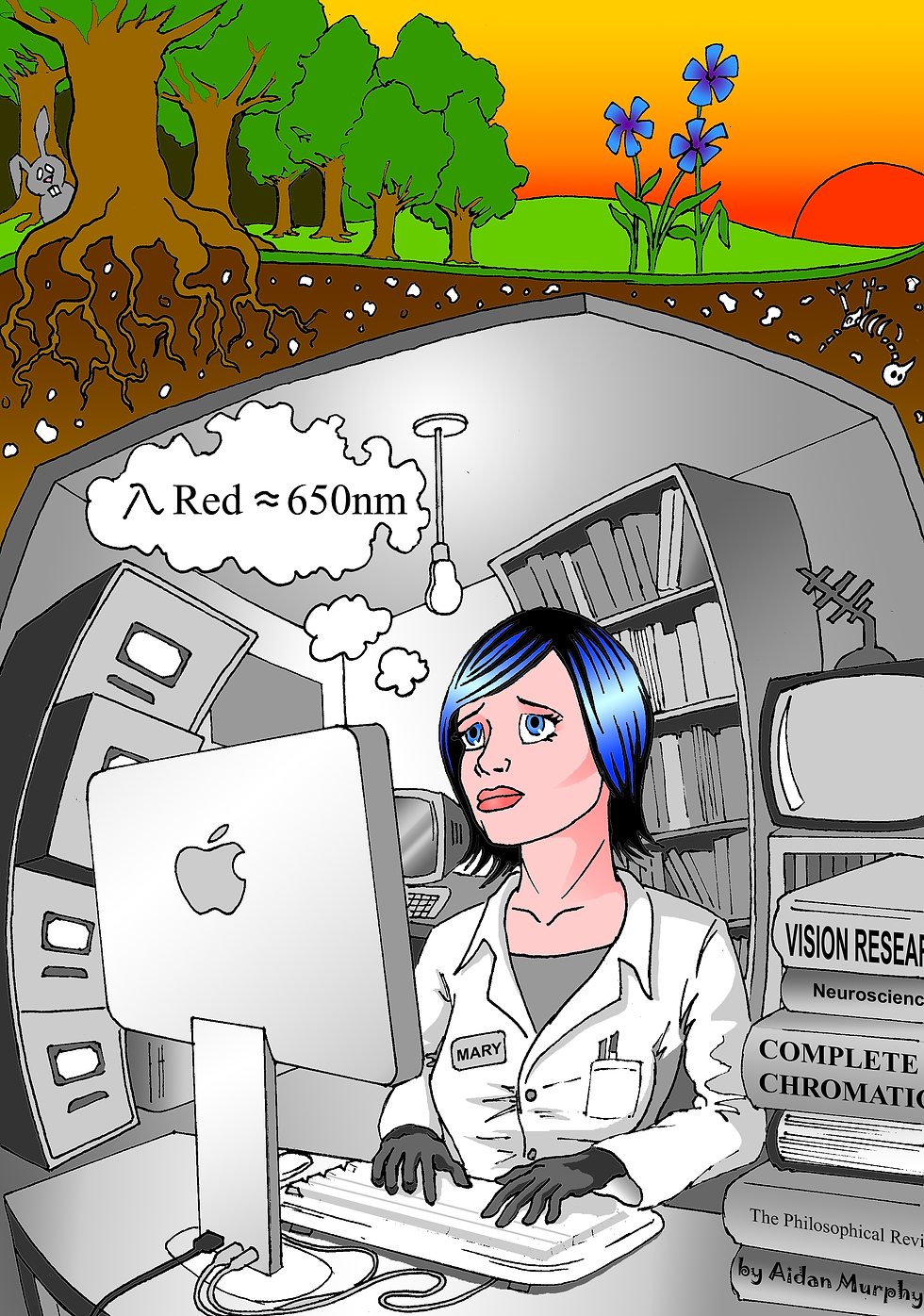

Mary’s Color Scientist Thought Experiment: The "Mary the Color Scientist" experiment underscores this irreducibility. Mary, despite knowing all physical facts about colour, gains a qualitatively new understanding upon experiencing red. This demonstrates that subjective experience, or qualia, is fundamentally distinct from objective knowledge.

Image Credit: Wikipedia

Ned Block’s Challenge to Materialism: Ned Block critiques materialist explanations of consciousness through a thought experiment called "China Brain", involving a vast network of people simulating brain activity. Even with immense complexity and interconnectivity, such a system would not develop subjective experience. This suggests that consciousness arises from something beyond physical interactions or complexity, posing a profound challenge to the view that the brain's material processes alone generate consciousness.

Image Credit: Wikipedia

These perspectives illuminate the "hard problem" of consciousness—its qualitative and subjective nature that resists explanation in purely physical or mathematical terms.

Panpsychism: Consciousness as a Fundamental Reality

David Chalmers, a prominent philosopher, proposes panpsychism, the idea that consciousness is a fundamental feature of the universe and exists everywhere. Chalmers finds this appealing for two reasons:

The Problem of Experience: Material explanations fail to account for subjective experience (qualia). If consciousness underpins reality, it naturally explains how experience arises.

The Substance of Structure: Drawing from Aristotle's distinction between "stuff" and "structure," panpsychism suggests consciousness is the "stuff" underlying the universe’s physical "structure."

Timothy Sprigge and Absolute Idealism: Oxford philosopher Timothy Sprigge, who is a huge fan of Advaita Vedanta, reinforced this perspective with his work, The Vindication of Absolute Idealism. He posited that consciousness—not matter—is the ultimate reality, countering the dominant materialist paradigm.

The Combination Problem: A significant critique of panpsychism is the "combination problem": if particles of consciousness exist everywhere, how do they combine into a unified mind? William James questioned this through an analogy: individual thoughts don’t combine to form a collective sentence, so how do discrete "conscious particles" form a single, cohesive consciousness?

Quantum Entanglement as a Solution: Modern thinkers like Jim Holt and Roger Penrose speculate that quantum entanglement might solve the combination problem. Entangled particles, which act as a single unit despite vast distances, could provide a model for how consciousness unifies in living brains—a hypothesis dubbed "quantum psychology."

Panpsychism opens profound questions about reality, bridging philosophy, neuroscience, and quantum physics, while pointing to consciousness as an omnipresent feature of existence.

Image Credit: Reddit

Advaita Vedanta’s Perspective on Consciousness and Reality

Advaita Vedanta offers a profound lens to address the challenges of consciousness, rooted in the principle that Atman (Self) is Brahman (Ultimate Reality). This non-dual philosophy asserts that the individual self and the universe are one indivisible reality. Modern parallels, like David Chalmers’ differentiation between external information (physics) and internal experience (consciousness), echo this Vedantic insight.

The Subject-Object Distinction

Vedanta uniquely distinguishes consciousness from the mind and objects:

Objects: Anything experienced, including thoughts, emotions, and perceptions.

Subject: Consciousness, the experiencer itself—pure, unchanging, and self-illuminating.

This clarity dissolves the “combination problem” in panpsychism. Consciousness, as the ultimate subject, does not aggregate or combine—it simply illuminates all objects and experiences.

The Dream Analogy

Vedanta likens the universe to a dream, as discussed in the Mandukya Upanishad by Gaudapada. The dream analogy resonates with Jim Holt's remark that reality might be "the dream of a mad philosopher." Just as a dream is real only to the dreamer, the perceived universe is real only to the mind but arises from the substrate of consciousness.

The Nature of Experience in Advaita Vedanta

In Advaita Vedanta, experience is defined as the interaction between consciousness and an object. Consciousness itself is pure, self-luminous, and universal, while objects include everything experienced—thoughts, emotions, sensory inputs, and physical forms.

How Experience Arises

Consciousness illuminates objects, creating the phenomenon of experience.

For example, just as a hand becomes visible under light but doesn’t produce light, consciousness reveals objects without being produced by them.

The mind, functioning as an "inner instrument" (antahkarana), processes these objects, integrating them through the ego (ahamkara), which appropriates experiences as "I see," "I feel," or "I think."

Consciousness, Mind, and the Brain

Modern neuroscience identifies strong correlations between brain activity and conscious experiences, often interpreting these findings to suggest that the brain generates consciousness. From the Advaita Vedantic perspective, this interpretation is fundamentally flawed.

The Role of the Brain

In Vedanta, the brain is regarded as a tool or instrument that facilitates the presentation of objects (both internal, like thoughts, and external, like sensory data) to consciousness. It does not create consciousness but serves as a medium through which experiences are structured and transmitted. The activities of neurons and neural networks correspond to the processing of sensory and cognitive inputs, akin to how a projector processes film to display an image.

Consciousness as Independent and Unchanging

Vedanta asserts that consciousness is not contingent upon the brain. It is independent, ever-present, and unchanging. While brain states may alter the content of experience—shaping perceptions, emotions, or thoughts—these changes affect only the objects of consciousness, not the witnessing consciousness itself.

Why the Mistake Happens

Brain activity is intricately tied to the objects we experience, so the assumption arises that the brain is the source of experience.

However, just as light makes a screen visible without being produced by the screen, consciousness illuminates objects without being created by the brain.

The brain’s role is analogous to a lens or filter, shaping the form of experience without altering the essence of consciousness.

The Ego as an Instrument

In Advaita Vedanta, the ego (ahamkara) is defined as "Abhimanatmika Antahkaranavritti", which means the appropriating function of the inner instrument (antahkarana). This function integrates sensory and mental activities into a coherent "I," creating the sense of individuality and ownership, as in "I see" or "I think." However, Vedanta clarifies that this ego is not the true self but a modification (vritti) of the mind.

"Abhimanatmika Antahkaranavritti" can be broken down as follows:

Abhimanatmika: Refers to the function or quality of appropriation or identification. It signifies the tendency to ascribe ownership or association, such as "I see," "I think," or "This is mine."

Antahkarana: The "inner instrument," which encompasses the mind, intellect, memory, and ego in Vedantic thought.

Vritti: A mental modification or function.

Thus, the phrase describes the ego (ahamkara) as a particular function of the inner instrument that appropriates experiences and integrates them into a sense of "I."

However, Vedanta emphasizes that the ego is not the true self. It is merely a transient construct observed by the unchanging consciousness, which is the true essence of the self (Atman). The ego’s role is analogous to a lens that focuses disparate inputs, yet it is itself an object of observation within consciousness.

States Where the Ego Recedes

Deep Sleep: In deep sleep, the ego dissolves temporarily. There is no "I" thinking or experiencing during this state, yet upon waking, one recalls having experienced peace or nothingness. This indicates that consciousness persists independently of the ego.

Intense Focus (Flow States): In moments of deep concentration, such as during meditation, artistic creation, or skilled activity, the ego fades into the background as the mind fully engages with the task. Despite this, consciousness remains intact, illuminating the experience without the interference of an "I."

Implications for Self-Realization

Recognizing the ego as an instrument, rather than the true self, is a pivotal step in Advaita Vedanta. It shifts identification away from the fluctuating, limited ego toward the pure, boundless consciousness that underlies all experience. This understanding fosters liberation (moksha), freeing one from the illusions and attachments associated with the ego’s narrative.

This Vedantic distinction highlights a subtle but profound shift in understanding: consciousness is the substratum of all experiences, while the brain is part of the objective world that it reveals. This understanding resolves the "combination problem" by recognizing that consciousness itself is singular and universal, while the ego and mind merely coordinate activities at the individual level. Experience thus arises when consciousness encounters objects, revealing the unity underlying all distinctions.

Bridging Western Ideas and Advaitic Philosophy

Modern explorations of consciousness, as seen in the work of physicists like Roger Penrose and philosophers like David Chalmers, push the boundaries of understanding but often stop at recognizing consciousness as a profound mystery. Vedanta begins where this inquiry ends.

In the Bhagavad Gita (9.4), Krishna states: Mayā tatam idam sarvam jagad avyaktamūrtinā

I pervade this entire universe in my unmanifest form. Here, Krishna identifies consciousness (chit) as the substratum of all existence.

Consciousness as the Substratum

Western science often views the universe as material, with consciousness arising within it. Vedanta reverses this perspective: the universe is an appearance within consciousness. This is likened to waves in water or a pot in clay. Waves are not entities with water inside; they are forms imposed upon water. Similarly, the universe is not a container of consciousness; rather, it is an expression within the field of pure existence.

Krishna expands this idea further, stating:

Mat-sthāni sarva-bhūtāni, na cāhaṁ teṣv avasthitaḥ.

All beings are in me, but I am not in them.

This paradox captures the Advaitic insight: consciousness pervades all, but it is not limited by the forms or entities it pervades. While everything exists as an appearance within Brahman, Brahman remains untouched and independent, transcending the apparent universe.

In the Bhagavad Gita (9.5), Krishna introduces one of the most profound insights:

Na ca mat-sthāni bhūtāni paśya me yogam aiśvaram.

None of these beings are in Me. Witness the magic of my power—Maya.

This verse marks a dramatic shift in understanding. Earlier, Krishna stated that all beings are in Him, yet here, He asserts the opposite. The key lies in the concept of Maya—the creative power through which the universe appears yet has no independent existence.

Appearance vs. Reality

Krishna clarifies that Brahman (pure consciousness) is not a container holding the universe. Just as a podium does not hold wood, but rather, the podium exists as a name and form imposed upon wood, the universe exists as an appearance within Brahman.

Through this lens:

The universe appears in Brahman but is not a separate reality.

Names, forms, and transactions (Nama-Rupa Vyavahara)—what we call reality—are superimpositions upon consciousness.

Brahman remains unchanged, just as water remains water whether it appears as a wave or stillness.

Advaita’s Expansion Beyond Science

Where modern physics and philosophy theorize, Advaita provides experiential clarity. By inquiring into the nature of self (Atman), one realizes it is identical to Brahman, the infinite consciousness. This recognition shifts the paradigm: from seeing the universe as a collection of objects to perceiving it as a unified field of consciousness.

In bridging these perspectives, Advaita not only addresses the "hard problem" of consciousness but also dissolves it by redefining the very notions of subject and object. This offers a deeper understanding that transcends the materialistic and dualistic frameworks of the West.

The Ultimate Realization

This Advaitic perspective harmonizes Western inquiries into the fabric of reality. Science grapples with understanding consciousness within the universe, but Vedanta reveals consciousness as the sole reality in which the universe arises, exists, and dissolves.

Krishna’s teaching dismantles the fear of mortality and separateness. By recognizing our true nature as Brahman, we transcend duality, anxiety, and egoic attachments, achieving liberation (Jivanmukti). Like water taking various forms yet remaining unchanged, we realize our eternal, infinite essence—joyful, fearless, and free.

Conclusion

This blog explored the profound relationship between Western ideas of reality and Advaitic philosophy, drawing from Swami Sarvapriyananda's talk, "It from Bit from Chit." We delved into Krishna's teachings in the Bhagavad Gita, which describe consciousness as the substratum of all existence. From modern Western perspectives, like panpsychism and quantum theories, to Advaita Vedanta's nondual vision, we discussed where these approaches converge and diverge.

Western methods often grapple with defining consciousness through empirical means, facing challenges like the "hard problem." Panpsychism—a bridge idea—proposes consciousness as a universal property, yet it stops short of Vedanta’s ultimate insight: consciousness is the only reality (Brahman). While Western science seeks answers within matter and mind, Advaita redefines reality as the interplay of nama (name), rupa (form), and Maya (illusion), with consciousness as the unchanging ground.

This discussion marks the beginning of a journey. In subsequent blogs, we will further explore Advaitic and Buddhistic methods, the implications of these ideas on modern life, and how understanding consciousness transforms our experience of reality. Stay tuned!

Comments